[written by speculative fiction author and reviewer, Robert Hood]

Part 1: Nosferatu

It’s a safe bet to say that up until the 1980s vampire cinema was dominated by the mesmeric influence of Bram Stoker’s novel Dracula. The character itself, the gothic atmosphere — in fact, vampire lore as defined (and sometimes invented) by Stoker — held sway over the imaginations of creators and audiences alike for many decades. Vampires had existed in folklore from countries worldwide long before the Count appeared, but generally they didn’t translate to the screen. The vampire that really caught on was no undead peasant, village outcast, gypsy itinerant or mere blood-sucking demon. He was a warrior and, more importantly, an aristocrat.

Metaphorically this first vampire of popular film culture was the scourge of the rising middle classes. The latter’s ever-growing influence over post-industrial revolution society was still haunted by the spectre of the feudal system: rule by blood, not by merit. The aristocratic vampire Dracula became a symbol of this ancient threat. The metaphor would cling like a dusty shroud to the cinematic vampire for many decades, even into a world where democracy was triumphant.

If the threat of ancient blood is the central metaphor underlying the first decades of cinematic vampire narration, the second, and these days most prominent, metaphor is the fear of sexual seduction. It is barely there in the novel, a dim undercurrent and held at a distance. Cinema would gradually re-enforce and exploit this particular metaphor. And Dracula would lead the way.

Yet the Count wasn’t the first vampire to appear on film.

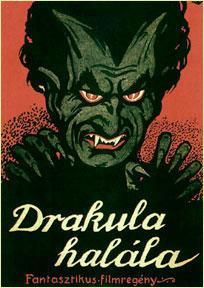

Drakula halaÌla-poster

Richard Oswald and Arthur Robison’s German silent film Nächte des Grauens (1916) (aka Night of Horror) featured vampire-like people and therefore holds claim to being the first vampire film ever made. Previously, the only vampires in evidence had been more along the lines of the one in Robert Vignola’s The Vampire (1913) — a “vamp” in the sense of a sexually predatory woman. Such vamps would become actual bloodsuckers further down the track.

The honour of being the first film adaptation of Stoker’s seminal vampire novel is generally assigned to a lost Hungarian film, Drakula halála [aka The Death of Dracula] from 1921 (directed by Károly Lajthay). Recent research casts doubt upon the claim, suggesting that Drakula halála was not based on the novel even though it drew on the same socio-historical events that inspired Stoker’s novel. Yet available images from the film seem to confirm the connection. Perhaps we will never know for sure. What is certain is that the first significant vampire film was Nosferatu: eine Symphonie des Grauens (Germany-1922; dir. F.W. Murnau) – a film that is still acknowledged as a masterpiece and a milestone in the history of cinema.

Despite name changes, it was obvious to everyone that Nosferatu was based on Dracula. This didn’t please the copyright holder (Bram Stoker’s widow), who took out a legal injunction against it. As part of the settlement, all known prints and negatives were destroyed. For a long time Nosferatu was thought lost. Fortunately, however, the legal purge wasn’t universally enforceable, though for some time prints tended to be hacked about somewhat. It is only since 2007, in fact, that a complete original copy has made its appearance on DVD.

The first thing that strikes the modern viewer about Count Orlok (as Dracula is named in Nosferatu) is that he lacks the sophisticated European ambiance that Bela Lugosi would later bring to the role. Here there is no sense that the vampire might have a sort of dangerous sexual appeal or at least an exotic romanticism that can make his victims vulnerable and suitably subservient. Graf Orlok, as played by Max Schreck, is demonic and rat-like — a species of supernatural vermin that brings plague and death with him. This is the vampire seen as retaining only a bestial vestige of humanity and being a carrier of disease. Note that the term “nosferatu”, which is referred to by Stoker in Dracula as Romanian for “vampire”, may in fact derive from the Greek “nosophoros”, meaning disease-bearing.

Nevertheless, despite all this, sex isn’t absent as a significant narrative motif in Nosferatu – as physically unappealing as its vampire is. Orlok (Dracula) becomes obsessed by Ellen Hutter (Mina Harker), so much so that it proves his downfall. It is here that Nosferatu diverges most noticeably from the original novel. Doomed by the vampire’s attentions, Ellen determines to sacrifice herself in order to destroy the creature and stop the killings, causing him to linger in her bedroom for too long, so that he is touched by the first rays of the rising sun and disintegrates. Ellen, too, dies, her sexual purity (and hence availability as wife) irrevocably compromised.

Ellen

Interestingly this appears to be the first introduction of the idea that daylight is deadly to vampires (in the novel, daylight merely limits Dracula’s powers). It is an idea that will become a mainstay of cinematic vampire lore. These days it is the absence of the bloodsuckers’ acute photosensitivity that seems deviant and requires explanation. Of course, as vampires (being demonic undead) are creatures of darkness, sensitivity to sunlight – as well as fear of the symbols of Christianity – makes perfect sense, at least in the Christian scheme of things and while the Church was society’s dominant spiritual authority.

Nosferatu Dies

[Coming up in Part 2: Lugosi to Christopher Lee]